In The Liberal Arts Tradition, Clark and Jain argue that the ancients considered gymnastics and music to be an essential component of early education (perhaps even THE essential components of early education.)

As a mother of many young children and a not-particularly-gymnasticly-oriented person, I have lots of questions. What do the ancients mean by gymnastic? Of what benefit is gymnastic training? How does a gymnastic education fit into the whole idea of a liberal arts education (that is, an education fit for free men)? And, in what manner did the medievals interpret the classical emphasis on gymnastic training?

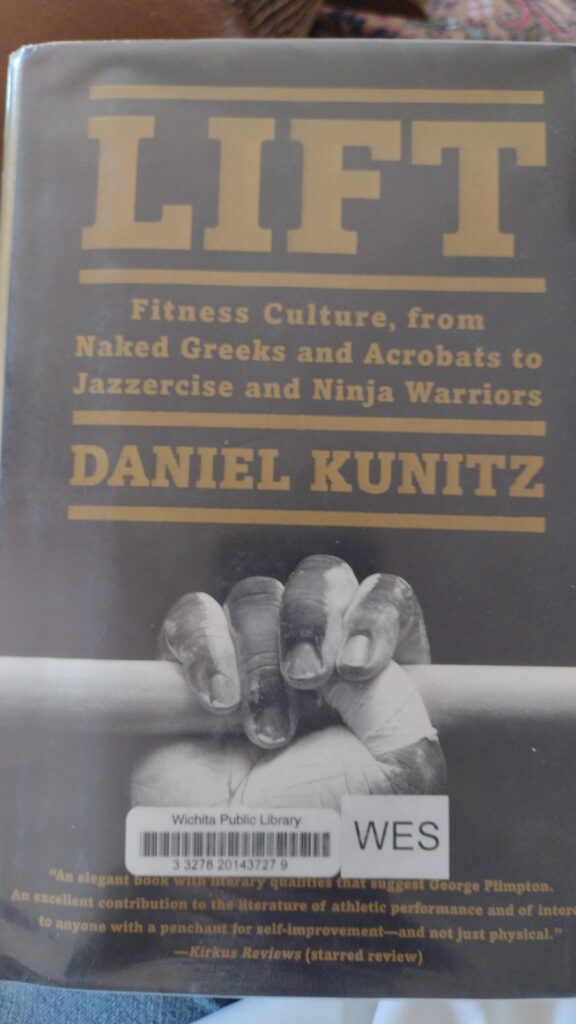

When I saw Daniel Kunitz’s Lift: Fitness Culture from Naked Greeks and Acrobats to Jazzercise and Ninja Warriors in my local library’s catalog, I hoped it could help in answering these questions.

Alas, it was not to be.

Kunitz seems much more interested in telling the story of his beloved Crossfit and creating an ancient mythology for it than in uncovering a historical understanding of fitness. He mentions that “In Athens, the three great gymnasia – Plato’s Akademy, Aristotle’s Lykeion, and the Cynosarges – were also sites of the era’s three major philosophical traditions, directed by philosopher-athletes” but offers no assistance in understanding the interplay between philosophy and athletics.

For an understanding of the early Christian attitude toward athletics, Kunitz falls even further short, stating without reference that “Christian denigration of the body as inherently sinful… certainly contributed significantly to the deterioration of athletics in the Roman era as well as in the Middle Ages” and leaving the whole Christian conception of the body there.

Kunitz does somewhat better at detailing a history of modern fitness, but his own obsession with Crossfit and the “New Fitness Frontier” clouds his ability to tell a clean story. He derides an emphasis on fitness for the sake of slimming down, but fails to make a good case for why fitness for the sake of looking like Hercules is better. He is dismissive of jogging and other aerobic pursuits as pointless (despite advocates stated desire to either improve cardiovascular health or to attain or maintain healthy weight), but fails to make a compelling case for the endless improvement (always seeking a new personal best) that he considers the ideal.

The optimization of the body is Kunitz’s goal – and perhaps the goal of fellow members of the New Fitness Frontier – but such a goal falls flat to my mind. The body is not an end in itself. It exists for a higher goal – the glory of God. So, for me, fitness is not about achieving my body’s greatest potential but about being fit to accomplish the purposes I know God has for me: fit to serve as my husband’s helpmeet, fit to mother and educate my children, fit to serve within my church and community however God should lead, and so forth.

Which means my search to better understand the meaning and value of “gymnastic education” as conceived by either the ancients or the medievals continues.