Childbirth stories never fail to pique my interest. Birth has been a passion of mine since I was young, reading my mom’s copy of Rahimah Baldwin’s Special Delivery. But since I’ve become a mother, my interest in childbirth stories has only increased.

So when the headline “Focus On Infants During Childbirth Leaves U.S. Moms In Danger” showed up in my newsreader, I clicked through to NPR’s report. And when I finally got the time to read the whole thing (it took several sittings because, hello, newly pregnant mother of a toddler and an infant), the story hit home in a way I wish it hadn’t.

The statistics are nothing new for me. The United States does a terrible job of keeping pregnant and postpartum women alive when compared to the rest of the developed world. I knew that. But this is a story with a face. The face of a woman with preeclampsia, with HELLP syndrome – a woman with what I had. A woman who died, leaving her baby behind.

There were warning signs. Signs that weren’t heeded. There were lots of opportunities to save her life. But when she or her husband suggested that preeclampsia might be the problem, they were pooh-poohed. And she died.

The text of the article hinted at rather than driving home the point the headline made: “Focus on Infants during Childbirth Leaves U.S. Moms in Danger” – but I couldn’t help but relive my own experiences.

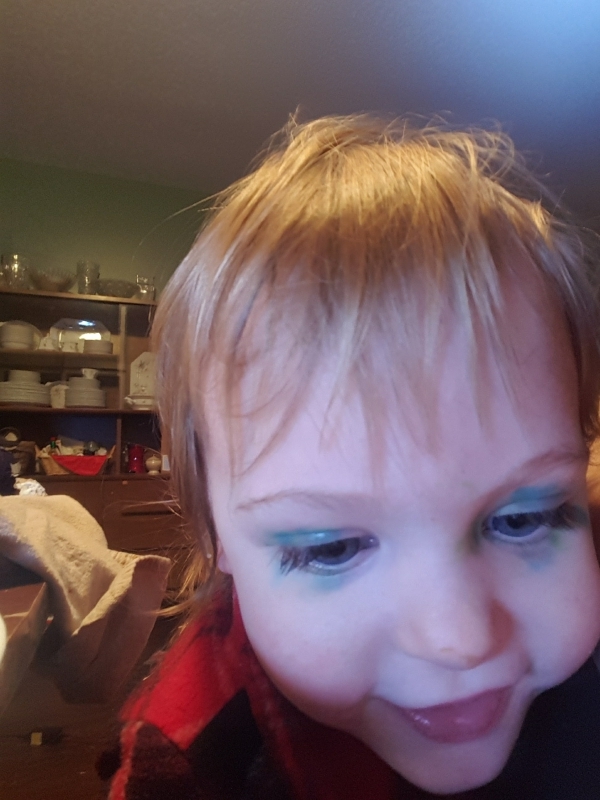

When I think back to my hospitalizations with Tirzah Mae and Louis, one of the hardest things for me to deal with was how the focus shifted from me to the babies the moment they were born. Before they were born, I was the patient. The nurses checked on me hourly. Every care was taken to keep my blood pressure low and to keep the baby inside me healthy.

But once they were born, it was as if a switch was flipped. Never mind that I had the exact same (life-threatening) condition I’d had before the babies were born (now with major abdominal surgery added on top of it). I was no longer carrying a baby, so I would be just fine. My baby was the important one. It was as if only one of us could be the patient. My turn was over and it was the baby’s turn.

Thankfully, with Tirzah Mae, I started improving after her birth and continued to improve.

With Louis, a medical error – a resident forgetting to prescribe me my blood pressure meds when he discharged me on a Friday afternoon four days postpartum – could have meant my death. By the grace of God, I took my blood pressure that Saturday afternoon just as I had every day of my pregnancy since my morning blood pressures had started to rise near the beginning of the third trimester. My blood pressure was at critical levels.

Rather than going to the hospital to hold and feed my baby on his fifth day on the outside, I traveled to the hospital for another purpose – to live to hold and feed my baby again. I spent hours in the ER getting one dose after another after another of IV labatelol. It took five doses to get my blood pressure back down.

I’m not angry with the nurses, with the doctors, not even with the resident who failed to prescribe me a blood pressure med on discharge. But I am angry with a system that only considers a woman’s health important inasmuch as the baby is kept healthy. Why can there only be one patient?

Is it not just as important that these babies we rightly fight to keep alive and well in our NICUs have mothers who are alive to care for and love them?

Why must there only be one patient?